It’s the most famous chord in popular music – a clarion call of Technicolor dissonance heralding the birth of a bright new era in pop music. The clanging chord that launched The Beatles’ first movie A Hard Day’s Night (1964) has been the focus of endless debate and analysis for over fifty years. Inscrutable and impossible to duplicate, even guitarist George Harrison could not quite capture its power in live performance, and with very good reason. As with most of The Beatles’ best work in the recording studio, its magic was partly due to the hidden efforts of their legendary producer and arranger, Sir George Martin.

Faced with a last-minute deadline to write the title song that would begin their debut movie, composers John Lennon and Paul McCartney quickly brought their new composition to the recording studio and played the tune for their producer. Immediately, George Martin sensed what was needed to enhance the song, as he recalled in a 2002 interview: “I said, ‘If this is going to be the opening music for the film, we’ve got to start with something fairly sensational. It’s got to attract everybody’s attention.’ So John said ‘What do you reckon?’ I said ‘How about one single chord that’s gonna knock people’s socks off.’ Suddenly he did this ‘twaaaaang!’ I said ‘That’s it! Great! We’ll stick that on the front.’ And, do you know, to this day I still don’t know what that chord was, but it’s a very good one.”

As ever, Martin was being modest in downplaying his own contributions. Listen closely to that chord and what do you hear? A G major guitar chord perhaps, with a suspended fourth or minor seventh added to the mix? In truth, Harrison’s Rickenbacker 360 twelve string electric guitar and Lennon’s Gibson J-160 acoustic are actually both playing a traditional first position F chord with G added as top note (Fadd9). With McCartney’s Hofner bass contributing a sustained high D note, we can hear the familiar sound taking shape, but the real magic comes from producer Martin’s musical input. By taking that simple Fadd9 guitar chord and subtly overdubbing a simple piano triad consisting of D-G-D played below middle C, Martin succeeded in baffling thousands of musicians for almost half a century. His contribution as phantom pianist on A Hard Day’s Night (he can also be heard doubling the low register guitar solo note-for-note on piano) perfectly encapsulated the crucial, unheralded role he played as producer of The Beatles. As he later acknowledged about the killer opening chord: “It set the tone for the song, and for the whole film because we (the audience) knew that what was going to follow was going to be dramatic, wonderful, funny, exciting, and everything else.”

The role George Martin played in guiding The Beatles’ careers during their early years cannot be overestimated, and his involvement with their material produced for A Hard Day’s Night exemplified his approach and his value to the group. “My job was to parcel the thing up, make it tidy, and tell the boys how long (the recording) had to be,” he remembered, as well as determining other important issues such as “where we would put the song (in the movie), how many times we would do it, where we would have a solo, how the beginning should start, and how to make it finish.”

In one of the key scenes of A Hard Day’s Night, The Beatles finally manage to break free from their perennial confines of hotel rooms, transportation and TV studios, and playfully relish the freedom of an isolated field, away from the pressures of fans, managers, and work commitments. Here, McCartney’s classic tune Can’t Buy Me Love provides the perfect musical accompaniment, and offers another instance of George Martin’s musical nous coming into play, where he devised a clever way to open and close the song. “In the case of Can’t Buy Me Love, I didn’t like the idea of going straight in as Paul did (into the verse),” he explained. “I said, ‘You know, you’ve got a good hook here’ (sings chorus). I said ‘Let’s use that and make that an introduction.’ And that makes a beginning – people want now to hear more, so that’s exactly what we did.”

The melodic appeal and harmonic sophistication of The Beatles’ music reached new heights in A Hard Day’s Night. The harmonic friction of the title tune, with its discordant opening and Mixolydian ambiguities (performed in the key of G but littered with F major chords throughout) typified the ear-catching nature of their compositions. Lennon’s If I Fell also demonstrated their appreciation of advanced chords and intuitive musical knowledge. Opening with an eight bar introduction in the key of Db, the composition gradually resolves into the key of D for the verse, and then easily incorporates a vast array of diminished, ninth, and minor seventh chords – unheard of at the time for a pop group writing their own material.

Similarly, McCartney’s And I Love Her continued his favourite device of writing a tune in the key of E major but starting the song with an F# minor chord (as also heard in All My Loving from the band’s previous album, With the Beatles). Here, the verse resolves with an E6 chord, incorporating the C# note from the first chord of the song and leading the way to the interlude in C# minor. The song’s imaginative arrangement, favouring classical guitar and claves over electric guitars and vocal harmonies, also reaffirmed the important role George Martin played in providing the perfect setting for each individual composition.

Aside from his crucial role as producer and musical soundboard to his prodigious young band, helping to bring shape and structure to their cache of irresistible songs, George Martin also scored a handful of memorable underscore cues throughout A Hard Day’s Night. Using the melodies and songs of The Beatles as his working material, Martin’s aim was to showcase their music in the best possible light. “I remember talking to some mums and dads who didn’t like The Beatles,” he recalled. “They didn’t like the moptops image and the raucousness… and they couldn’t hear the music for the noise. So if they got a song like All My Loving, they wouldn’t even start to listen to it. We had to convert them – we had to make them aware that this music was great. And one of the ways of doing that in the film was to underscore with the tunes. “

The eclectic nature of Martin’s fully orchestrated cues proved how flexible The Beatles’ music could be when handled with respect and sensitivity. He transforms A Hard Day’s Night from a 4/4 driving pop song into a jazzy waltz for tenor saxophone, reverting to 4/4 only occasionally to increase the excitement levels. Switching between time signatures with consummate ease, its relaxed manner and rhythmic pulse bears more resemblance to Dave Brubeck’s Take Five than a typical Beatles tune, such is the extent of the makeover.

Conversely, Lennon’s I Should Have Known Better is turned into a brass driven twist number, with pounding, frenetic rhythms and an electric guitar taking the place of the lead vocals. Martin’s underscore treatment of And I Love Her – the major ballad of the movie – sees him retain the classical guitar motif and the clave and bongo percussion from The Beatles’ original arrangement. He also adds a touch of dramatic colour by incorporating shimmering string flourishes, rhapsodic melodies, harp glissandos, and most notably a distinctive high register descending piano arpeggio which dominates the new orchestration.

In the most acclaimed sequence of A Hard Day’s Night, we find drummer Ringo Starr meandering alone by a canal, accompanied by George Martin’s popular arrangement of This Boy, (subtitled ‘Ringo’s Theme’ for the movie), and scored for orchestra and electric guitar. As he recalled: “(This Boy) was a strange one to choose (for the underscore) but we needed a mood piece for Ringo going off by himself – slightly melancholy. I think it was Dick (director Richard Lester) who suggested using This Boy as a theme song, and I just scored it for orchestra and I used electric guitar – rather like the James Bond (Theme) guitar. In fact we had Vic Flick playing it, who played the original James Bond (guitar theme) – very low down. It seemed to work, I think.”

The James Bond connection is well founded, with guitarist Flick employing a similar tone to his famous work with Bond theme composer Monty Norman. However, the mood here is more subdued, with the long sustained notes – devoid of vibrato – establishing a more plaintive mood, a feeling of isolation and dejection. The guitar is shadowed initially by a brass trio, echoing the original harmonies of The Beatles’ vocal arrangement, when suddenly the chorus arrives and the clouds disperse, the guitar fades away and the brass emerge to lift the melody to higher and higher levels, spurred on by some beautiful rhythmic support from the string section.

This Boy (Ringo’s Theme) is also notable for the identity of the second guitarist who plays on the recording alongside Vic Flick. We all know of Eric Clapton’s famous participation on The Beatles’ 1968 recording of While My Guitar Gently Weeps, but who could have guessed that, four years earlier, another guitar god had featured on a Beatles soundtrack recording – Led Zeppelin maestro Jimmy Page. Then working as a session musician, the 20 year old Page had entered Abbey Road studios with no prior warning of his assignment, as he recalled with astonishment during an interview in 2010: “I turned up and, lo and behold, there was George Martin.” Driving the performance with a propulsive acoustic rhythm guitar part, Page gratefully acknowledged: “I recognised the music and realised what it was.”

Today, A Hard Day’s Night is considered to be one of the greatest – and most influential – movies of all-time, inspiring countless musicians and film-makers alike from its moment of release. The quality of the music in the film is reflected by the continued success of its accompanying album by The Beatles, which is rightly recognised as one of the seminal albums of their illustrious career. Meanwhile, George Martin’s underscore cues from A Hard Day’s Night proved so popular that his work was nominated for an Academy Award, and the tracks were also given their own release as vinyl singles in August 1964, shortly after the movie’s successful opening. Long out of print, the recordings received a welcome re-release in America last year. As well as producing The Beatles’ regular albums, George Martin would later collaborate with the band on the silver screen again in 1968, writing a celebrated score to accompany their classic animated movie Yellow Submarine.

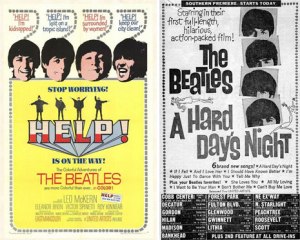

As for The Beatles, the success of A Hard Day’s Night quickly led to the filming of a second movie the following year, titled Help! (1965). This time George Martin was not asked to provide underscoring for the new film, even though his work on A Hard Day’s Night had been received with considerable critical acclaim. In spite of producing all The Beatles’ new tracks for Help!, Martin was overlooked by director Richard Lester in favour of rising composer Ken Thorne. It was a decision that would mark the start of an enduring professional association between composer and director, lasting well into the 1980s and including such movies as How I Won the War (1967), The Magic Christian (1969) and Superman III (1983).

In keeping with Martin’s earlier work for A Hard Day’s Night, Thorne made special use of The Beatles’ melodies when creating many of his underscore cues for Help! His From Me To You Fantasia playfully takes the group’s hit pop song From Me To You and reinterprets it as a mood piece of mystery and suspense, with pizzicato strings, droning sitars, hanging celeste chords and atonal brass flourishes. His score is also notable for a number of James Bond pastiches (echoing the plot of the movie), including The Bitter End, where he first creates an atmosphere of espionage by incorporating tremolo violins, pedal point strings, vibraphone arpeggios and celeste glissandos, before the whole work takes off with a James Bond-style guitar arrangement of Lennon’s You Can’t Do That played on the low strings over a jaunty rhythmic accompaniment and piercing brass fanfares.

In a move that would have far reaching consequences upon The Beatles’ later development, Thorne also incorporated an orchestra of Indian instruments into his score, producing a frenetic raga as accompaniment to The Chase, with sitars intertwining improvisational melodies over a single chord drone. Most memorably, he also devised Another Hard Day’s Night – an ingenious medley of Beatles tunes as played by sitars, bansuri, tamboura, and tabla percussion. With A Hard Day’s Night segueing into Can’t Buy Me Love and I Should Have Known Better, it is perhaps the high point of the movie’s clever, eclectic underscore. The filming of the accompanying scene in the movie, featuring Indian musicians performing in a London restaurant with their native instruments, would also indirectly pique George Harrison’s interest in Eastern music and gradually bring about a fundamental change in the direction of The Beatles’ music.

The handful of new songs contributed by The Beatles to Help! illustrate how the band continued to hone their song-writing abilities, with Lennon borrowing a trick from McCartney’s earlier efforts by launching the title song with a supertonic chord (B minor), before resolving to the tonic chord of A major by the start of the verse. Their love of flatted sevenths led to further usage of Mixolydian modes in the vocal harmonies of songs such as Ticket to Ride and You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away, while the latter’s arrangement also demonstrates the band’s widening appreciation of orchestral instruments, making novel use of two flutes performing the closing theme in octave unison.

Over a half-century on from the creation of A Hard Day’s Night and Help!, the musical legacy of The Beatles remains as fresh and inventive as ever. Time has not dimmed the appeal nor diluted the quality of their work, and it is hard to imagine how the world would be today without their pervading influence. It is somewhat unfortunate that the vast musical contributions of George Martin and Ken Thorne to these two classic movies have been neglected through the years, but at least they can take consolation in the knowledge that their work will live on in the hearts and minds of generations to come. For as long as people continue to watch classic movies, and continue to listen to timeless music, then their place in movie and music history is assured.

Sources:

“A Hard Day’s Night”, Buena Vista DVD Documentary, 2002

The Beatles Complete Scores. Wise Publication. Print.

“Jimmy Page Interview by Tony Barrell from 8/22/10 in the Sunday Times.” *. Web.